DB cooper

D. B. Cooper is a media epithet popularly used to refer to an unidentified man who hijacked aBoeing 727 aircraft in the airspace betweenPortland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington, on November 24, 1971. He extorted $200,000 in ransom (equivalent to $1,210,000 in 2017) and parachuted to an uncertain fate. Despite an extensive manhunt and protracted FBIinvestigation, the perpetrator has never been located or identified. It remains the only unsolved case of air piracy in commercial aviation history.[1][2][3]

Available evidence and a preponderance of expert opinion suggested from the beginning that Cooper probably did not survive his high-risk jump, but his remains were never recovered.[4] The FBI nevertheless maintained an active investigation for 45 years after the hijacking. Despite a case file that grew to over 60 volumes over that time period,[5] no definitive conclusions have been reached regarding Cooper's true identity or whereabouts if he survived the jump. The suspect purchased his airline ticket using thealias Dan Cooper, but because of a news media miscommunication he became known in popular lore as "D. B. Cooper".

Numerous theories of widely varying plausibility have been proposed over the years by investigators, reporters, and amateur enthusiasts.[1][6] A young boy discovered a small cache of ransom bills along the banks of the Columbia River in February 1980. The find triggered renewed interest but ultimately only deepened the mystery, and the great majority of the ransom remains unrecovered.

The FBI officially suspended active investigation of the case in July 2016, but the agency continues to request that any physical evidence that might emerge related to the parachutes or the ransom money be submitted for analysis.[7]

Hijacking

On Thanksgiving eve, November 24, 1971, a middle-aged man carrying a black attaché case approached the flight counter ofNorthwest Orient Airlines at Portland International Airport. He identified himself as "Dan Cooper" and used cash to purchase a one-way ticket on Flight 305, a 30-minute trip to Seattle.[8]

Cooper boarded the aircraft, a Boeing 727-100 (FAA registration N467US), and took seat 18C[1] (18E by one account,[9] 15D by another[10]) in the rear of the passenger cabin. He lit a cigarette[11] and ordered a bourbonand soda. Fellow passengers described him as a man in his mid-forties, between 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) and 6 feet (1.8 m) tall. He wore a black lightweight raincoat, loafers, a dark suit, a neatly pressed white collared shirt, a black clip-on tie, and a mother of pearl tie pin.[12]

Flight 305 was approximately one-third full when it took-off on schedule at 2:50 p.m.,PST. Shortly after takeoff, Cooper handed a note to Florence Schaffner, the flight attendant situated nearest to him in a jump seat attached to the aft stair door.[1] Schaffner assumed that the note contained a lonely businessman's phone number and dropped it unopened into her purse.[13] Cooper leaned toward her and whispered, "Miss, you'd better look at that note. I have a bomb."[14]

The note was printed in neat, all-capital letters with a felt-tip pen.[15] Its exact wording is unknown, because Cooper later reclaimed it,[16][17] but Schaffner recalled that the note indicated he had a bomb in his briefcase. After Schaffner read the note, Cooper directed her to sit beside him.[18] Schaffner did as requested, then quietly asked to see the bomb. Cooper cracked open his briefcase long enough for her to glimpse eight red cylinders[19] ("four on top of four") attached to wires coated with red insulation, and a large cylindrical battery.[20] After closing the briefcase, he dictated his demands: $200,000 in "negotiable American currency";[21] fourparachutes (two primary and two reserve); and a fuel truck standing by in Seattle to refuel the aircraft upon arrival.[22] Schaffner conveyed Cooper's instructions to the pilots in the cockpit; when she returned, he was wearing dark sunglasses.[1]

The pilot, William Scott, contacted Seattle–Tacoma Airport air traffic control, which in turn informed local and federal authorities. The 36 other passengers were given false information that their arrival in Seattle would be delayed because of a "minor mechanical difficulty".[23] Northwest Orient's president,Donald Nyrop, authorized payment of theransom and ordered all employees to cooperate fully with the hijacker's demands.[24] The aircraft circled Puget Soundfor approximately two hours to allow Seattle police and the FBI sufficient time to assemble Cooper's parachutes and ransom money, and to mobilize emergency personnel.[1]

Schaffner recalled that Cooper appeared familiar with the local terrain; at one point he remarked, "Looks like Tacoma down there," as the aircraft flew above it. He also correctly mentioned that McChord Air Force Base was only a 20-minute drive (at that time) from Seattle-Tacoma Airport. Schaffner described him as calm, polite, and well-spoken, not at all consistent with the stereotypes (enraged, hardened criminals or "take-me-to-Cuba"political dissidents) popularly associated withair piracy at the time. Tina Mucklow, another flight attendant, agreed. "He wasn't nervous," she told investigators. "He seemed rather nice. He was never cruel or nasty. He was thoughtful and calm all the time."[1] He ordered a second bourbon and water, paid his drink tab (and attempted to give Schaffner the change),[1] and offered to request meals for the flight crew during the stop in Seattle.[25]

FBI agents assembled the ransom money from several Seattle-area banks – 10,000 unmarked 20-dollar bills, most with serial numbers beginning with the letter "L" indicating issuance by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, and most from the 1963A or 1969 series[26] – and made amicrofilm photograph of each of them.[27]Cooper rejected the military-issue parachutes offered by McChord AFB personnel, instead demanding civilian parachutes with manually operated ripcords. Seattle police obtained them from a local skydiving school.[16]

Passengers released

At 5:24 p.m. Cooper was informed that his demands had been met, and at 5:39 p.m. the aircraft landed at Seattle-Tacoma Airport.[28]Cooper instructed Scott to taxi the jet to an isolated, brightly lit section of the tarmac and close each window shade[29] in the cabin to deter police snipers. Northwest Orient's Seattle operations manager, Al Lee, approached the aircraft in street clothes to avoid the possibility that Cooper might mistake his airline uniform for that of a police officer. He delivered the cash-filled knapsack and parachutes to Mucklow via the aft stairs. Once the delivery was completed, Cooper ordered all passengers, Schaffner, and senior flight attendant Alice Hancock to leave the plane.[30]

During refueling, Cooper outlined his flight plan to the cockpit crew: a southeast course toward Mexico City at the minimum airspeed possible without stalling the aircraft – approximately 100 knots (190 km/h; 120 mph) – at a maximum 10,000 foot (3,000 m) altitude. He further specified that the landing gear remain deployed in the takeoff/landing position, the wing flaps be lowered 15 degrees, and the cabin remainunpressurized.[31] Copilot William Rataczak informed Cooper that the aircraft's range was limited to approximately 1,000 miles (1,600 km) under the specified flight configuration, which meant that a second refueling would be necessary before enteringMexico. Cooper and the crew discussed options and agreed on Reno, Nevada, as the refueling stop.[32] With the plane's rear exit door open and its staircase extended, Cooper directed the pilot to take off. Northwest's home office objected, on grounds that it was unsafe to take off with the aft staircase deployed. Cooper countered that it was indeed safe, but he would not argue the point; he would lower it once they were airborne.[33]

An FAA official requested a face-to-face meeting with Cooper aboard the aircraft, which was denied.[34] The refueling process was delayed because of a vapor lock in the fuel tanker truck's pumping mechanism,[35]and Cooper became suspicious; but he allowed a replacement tanker truck to continue the refueling – and a third after the second ran dry.[1]

Back in the air

Boeing 727 with the aft airstair open

At approximately 7:40 p.m., the Boeing 727 took off with only five people onboard: Cooper, pilot Scott, flight attendant Mucklow, copilot Rataczak, and flight engineer H. E. Anderson. Two F-106 fighter aircraft were scrambled from McChord Air Force Base and followed behind the airliner, one above it and one below, out of Cooper's view.[36] ALockheed T-33 trainer, diverted from an unrelated Air National Guard mission, also shadowed the 727 before running low on fuel and turning back near the Oregon–Californiastate line.[37]

After takeoff, Cooper told Mucklow to join the rest of the crew in the cockpit and remain there with the door closed. As she complied, Mucklow observed Cooper tying something around his waist. At approximately 8:00 p.m., a warning light flashed in the cockpit, indicating that the aft airstair apparatus had been activated. The crew's offer of assistance via the aircraft's intercom system was curtly refused. The crew soon noticed a subjective change of air pressure, indicating that the aft door was open.[38]

At approximately 8:13 p.m., the aircraft's tail section sustained a sudden upward movement, significant enough to require trimming to bring the plane back to level flight.[39][40] At approximately 10:15 p.m., the aircraft's aft airstair was still deployed when Scott and Rataczak landed the 727 at Reno Airport. FBI agents, state troopers, sheriff's deputies, and Reno police surrounded the jet, as it had not yet been determined with certainty that Cooper was no longer aboard, but an armed search quickly confirmed his absence.[41]

Investigation

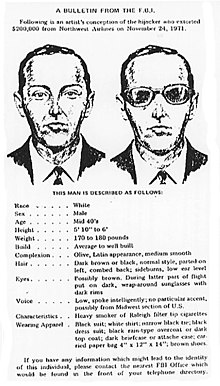

FBI agents recovered 66 unidentified latent fingerprints aboard the airliner.[3] The agents also found Cooper's black clip-on tie, his tie clip and two of the four parachutes,[42] one of which had been opened and two shroud lines cut from its canopy.[43] Authorities interviewed eyewitnesses in Portland, Seattle, and Reno, and all those who personally interacted with Cooper. A series of composite sketches was developed.[44]

Local police and FBI agents immediately began questioning possible suspects. An Oregon man named D. B. Cooper who had a minor police record was one of the firstpersons of interest in the case. He was contacted by Portland police on the off-chance that the hijacker had used his real name or the same alias in a previous crime. He was quickly ruled out as a suspect, but a local reporter named James Long, rushing to meet an imminent deadline, confused the eliminated suspect's name with the pseudonym used by the hijacker.[45][46] A wire service reporter (Clyde Jabin of UPI by most accounts,[47][48] Joe Frazier of the AP by others[49]) republished the error, followed by numerous other media sources; the moniker "D. B. Cooper" became lodged in the public's collective memory.[40]

A precise search area was difficult to define, as even small differences in estimates of the aircraft's speed, or the environmental conditions along the flight path (which varied significantly by location and altitude), changed Cooper's projected landing point considerably.[50] An important variable was the length of time he remained in free fall before pulling his ripcord—if indeed he succeeded in opening a parachute at all.[51]Neither of the Air Force fighter pilots saw anything exit the airliner, either visually or onradar, nor did they see a parachute open; but at night, with extremely limited visibility and cloud cover obscuring any ground lighting below, an airborne human figure clad entirely in black clothing could easily have gone undetected.[52] The T-33 pilots never made visual contact with the 727 at all.[53]

In order to conduct an experimental re-creation, Scott piloted the aircraft used in the hijacking in the same flight configuration. FBI agents, pushing a 200-pound (91 kg) sled out of the open airstair, were able to reproduce the upward motion of the tail section described by the flight crew at 8:13 p.m. Based on this experiment, it was concluded that 8:13 p.m. was the most likely jump time.[54] At that moment the aircraft was flying through a heavy rainstorm over theLewis River in southwestern Washington.[50]

Initial extrapolations placed Cooper's landing zone within an area on the southernmost outreach of Mount St. Helens, a few miles southeast of Ariel, Washington, near Lake Merwin, an artificial lake formed by a dam on the Lewis River.[55] Search efforts focused onClark and Cowlitz Counties, encompassing the terrain immediately south and north, respectively, of the Lewis River in southwest Washington.[56][57] FBI agents and sheriff's deputies from those counties searched large areas of the mountainous wilderness on foot and by helicopter. Door-to-door searches of local farmhouses were also carried out. Other search parties ran patrol boats along Lake Merwin and Yale Lake, the reservoir immediately to its east.[58] No trace of Cooper, nor any of the equipment presumed to have left the aircraft with him, was found.

The FBI also coordinated an aerial search, using fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters from the Oregon Army National Guard, along the entire flight path (known as Victor 23 in standard aviation terminology[59] but "Vector 23" in most Cooper literature[1][3][60]) from Seattle to Reno. While numerous broken treetops and several pieces of plastic and other objects resembling parachute canopies were sighted and investigated, nothing relevant to the hijacking was found.[61]

Shortly after the spring thaw in early 1972, teams of FBI agents aided by some 200 Armysoldiers from Fort Lewis, along with Air Force personnel, National Guardsmen, and civilian volunteers, conducted another thorough ground search of Clark and Cowlitz Counties for eighteen days in March, and then an additional eighteen days in April.[62] Electronic Explorations Company, a marine salvage firm, used a submarine to search the 200-foot (61 m) depths of Lake Merwin.[63] Two local women stumbled upon a skeleton in an abandoned structure in Clark County; it was later identified as the remains of a female teenager who had been abducted and murdered several weeks before.[64] Ultimately, the search operation—arguably the most extensive, and intensive, in U.S. history—uncovered no significant material evidence related to the hijacking.[65]

Search for ransom money

A month after the hijacking, the FBI distributed lists of the ransom serial numbers to financial institutions, casinos, race tracks, and other businesses that routinely conducted significant cash transactions, and to law enforcement agencies around the world. Northwest Orient offered a reward of 15% of the recovered money, to a maximum of $25,000. In early 1972, U.S. Attorney General John N. Mitchell released the serial numbers to the general public.[66] In 1972, two men used counterfeit 20-dollar bills printed with Cooper serial numbers to swindle $30,000 from a Newsweek reporter named Karl Fleming in exchange for an interview with a man they falsely claimed was the hijacker.[67]

In early 1973, with the ransom money still missing, The Oregon Journal republished the serial numbers and offered $1,000 to the first person to turn in a ransom bill to the newspaper or any FBI field office. In Seattle, the Post-Intelligencer made a similar offer with a $5,000 reward. The offers remained in effect until Thanksgiving 1974, and though there were several near-matches, no genuine bills were found.[68] In 1975 Northwest Orient's insurer, Global Indemnity Co., complied with an order from the Minnesota Supreme Court and paid the airline's $180,000 claim on the ransom money.[69]

Later developments

Subsequent analyses indicated that the original landing zone estimate was inaccurate: Scott, who was flying the aircraft manually because of Cooper's speed and altitude demands, later determined that his flight path was significantly farther east than initially assumed.[5] Additional data from a variety of sources—in particular Continental Airlines pilot Tom Bohan, who was flying four minutes behind Flight 305—indicated that the wind direction factored into drop zone calculations had been wrong, possibly by as much as 80 degrees.[70] This and other supplemental data suggested that the actual drop zone was probably south-southeast of the original estimate, in the drainage area of the Washougal River.[71]

Investigation suspended

On July 8, 2016, the FBI announced that it was suspending active investigation of the Cooper case, citing a need to focus its investigative resources and manpower on issues of higher and more urgent priority. Local field offices will continue to accept any legitimate physical evidence—related specifically to the parachutes or the ransom money—that may emerge in the future. The 60-volume case file compiled over the 45-year course of the investigation will be preserved for historical purposes at FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C.[72]

Physical evidence

The official physical description of Cooper has remained unchanged and is considered reliable. Flight attendants Schaffner and Mucklow, who spent the most time with Cooper, were interviewed on the same night in separate cities,[4] and gave nearly identical descriptions: 5 feet 10 inches (1.78 m) to 5 feet 11 inches (1.80 m) tall, 170 to 180 pounds (77 to 82 kg), mid-40s, with close-set piercing brown eyes and swarthy skin.[73]

In 1978, a placard printed with instructions for lowering the aft stairs of a 727 was found by a deer hunter near a logging road about 13 miles (21 km) east of Castle Rock, Washington, well north of Lake Merwin, but within Flight 305's basic flight path.[74]

In February 1980, eight-year-old Brian Ingram was vacationing with his family on theColumbia River at a beachfront known as Tina (or Tena) Bar, about 9 miles (14 km) downstream from Vancouver, Washingtonand 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Ariel. The child uncovered three packets of the ransom cash as he raked the sandy riverbank to build a campfire. The bills were significantly disintegrated, but still bundled in rubber bands.[75] FBI technicians confirmed that the money was indeed a portion of the ransom—two packets of 100 twenty-dollar bills each, and a third packet of 90, all arranged in the same order as when given to Cooper.[76][77] In 1986, after protracted negotiations, the recovered bills were divided equally between Ingram and Northwest Orient's insurer; the FBI retained fourteen examples as evidence.[66][78]Ingram sold fifteen of his bills at auction in 2008 for about $37,000.[79] To date, none of the 9,710 remaining bills have turned up anywhere in the world. Their serial numbers remain available online for public search.[26]The Columbia River ransom money and the airstair instruction placard remain the only bona fide physical evidence from the hijacking ever found outside the aircraft.[80]

In 2017, a group of volunteer investigators uncovered what they believe to be “potential evidence, what appears to be a decades-old parachute strap" in the Pacific Northwest.[81]This was followed later in August 2017 with a piece of foam, suspected of being part of Cooper's backpack.[82]

Subsequent FBI disclosures

In late 2007, the FBI announced that a partialDNA profile had been obtained from three organic samples found on Cooper's clip-on tie in 2001,[50] though they later acknowledged that there is no evidence that the hijacker was the source of the sample material. "The tie had two small DNA samples, and one large sample," said Special Agent Fred Gutt. "It's difficult to draw firm conclusions from these samples."[83] The Bureau also made public a file of previously unreleased evidence, including Cooper's 1971 plane ticket (price: $20.00, paid in cash),[84] and posted previously unreleased composite sketches and fact sheets, along with a request to the general public for information which might lead to Cooper's positive identification.[44][50][85]

They also disclosed that Cooper chose the older of the two primary parachutes supplied to him, rather than the technically superior professional sport parachute; and that from the two reserve parachutes, he selected a "dummy"—an unusable unit with an inoperative ripcord intended for classroom demonstrations,[50] although it had clear markings identifying it to any experienced skydiver as non-functional.[86] (He cannibalized the other, functional reserve parachute, possibly using its shrouds to tie the money bag shut,[50] and to secure the bag to his body as witnessed by Mucklow[37]) The FBI stressed that inclusion of the dummy reserve parachute, one of four obtained in haste from a Seattle skydiving school, was accidental.[84]

In March 2009, the FBI disclosed that Tom Kaye, a paleontologist from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, had assembled a team of "citizen sleuths", including scientific illustrator Carol Abraczinskas and metallurgist Alan Stone. The group, eventually known as the Cooper Research Team,[87] reinvestigated important components of the case using GPS, satellite imagery, and other technologies unavailable in 1971.[80] While little new information was gained regarding the buried ransom money or Cooper's landing zone, they were able to find and analyze hundreds of minute particles on Cooper's tie using electron microscopy.Lycopodium spores (likely from a pharmaceutical product) were identified, as well as fragments of bismuth andaluminum.[87]

In November 2011, Kaye announced that particles of pure (unalloyed) titanium had also been found on the tie. He explained that titanium, which was much rarer in the 1970s than it is today, was at that time found only in metal fabrication or production facilities, or at chemical companies using it (combined with aluminum) to store extremely corrosive substances.[88] The findings suggested that Cooper may have been a chemist or a metallurgist, or possibly an engineer or manager (the only employees who wore ties in such facilities at that time) in a metal or chemical manufacturing plant,[89] or at a company that recovered scrap metal from those types of factories.[90]

In January 2017, Kaye reported that rare earth minerals such as cerium and strontium sulfide had also been identified among particles from the tie. One of the rare applications for such elements in the 1970s was Boeing's supersonic transport development project, suggesting the possibility that Cooper was a Boeing employee.[91][92] Other possible sources of the material included plants that manufacturedcathode ray tubes, such as the Portland firmsTeledyne and Tektronix.[93]

Theories and conjectures

Over the 45-year span of its active investigation, the FBI periodically made public some of its working hypotheses and tentative conclusions, drawn from witness testimony and the scarce physical evidence.[94]

Cooper appeared to be familiar with the Seattle area and may have been an Air Force veteran, based on testimony that he recognized the city of Tacoma from the air as the jet circled Puget Sound, and his accurate comment to Mucklow that McChord AFB was approximately 20 minutes' driving time from the Seattle-Tacoma Airport—a detail most civilians would not know, or comment upon.[37] His financial situation was very likely desperate, as extortionists and other criminals who steal large amounts of money nearly always do so, according to experts, because they need it urgently; otherwise, the crime is not worth the considerable risk.[95] A minority opinion is that Cooper was "a thrill seeker" who made the jump "just to prove it could be done."[96]

Agents theorized that Cooper took his alias from a popular Belgian comic book series of the 1970s featuring the fictional hero Dan Cooper, a Royal Canadian Air Force test pilot who took part in numerous heroic adventures, including parachuting. (One cover from the series, reproduced on the FBI web site, depicts test pilot Cooper skydiving in full paratrooper regalia.[80]) Because the Dan Cooper comics were never translated into English, nor imported to the U.S., they speculated that he may have encountered them during a tour of duty in Europe.[80] The Cooper Research Team (see Ongoing investigation) suggested the alternative possibility that Cooper was Canadian, and found the comics in Canada, where they were also sold.[97] They noted his specific demand for "negotiable American currency",[22] a phrase seldom if ever used by American citizens; since witnesses stated that Cooper had no distinguishable accent, Canada would be his most likely country of origin if he were not a U.S. citizen.[98]

Evidence suggested that Cooper was knowledgeable about technique, aircraft, and the terrain. He demanded four parachutes to force the assumption that he might compel one or more hostages to jump with him, thus ensuring he would not be deliberately supplied with sabotaged equipment.[99] He chose a 727-100 aircraft because it was ideal for a bail-out escape, due not only to its aft airstair but also the high, aftward placement of all three engines, which allowed a reasonably safe jump without risk of immediate incineration by jet exhaust. It had "single-point fueling" capability, a recent innovation that allowed all tanks to be refueled rapidly through a single fuel port. It also had the ability (unusual for a commercial jet airliner) to remain in slow, low-altitude flight without stalling; and Cooper knew how to control its air speed and altitude without entering the cockpit, where he could have been overpowered by the three pilots.[100] In addition, Cooper was familiar with important details, such as the appropriate flap setting of 15 degrees (which was unique to that aircraft), and the typical refueling time. He knew that the aft airstair could be lowered during flight—a fact never disclosed to civilian flight crews, since there was no situation on a passenger flight that would make it necessary—and that its operation, by a single switch in the rear of the cabin, could not be overridden from the cockpit.[101] Some of this knowledge was virtually unique to CIA paramilitary units.[102]

In addition to planning his escape, Cooper retrieved the note and wore dark glasses, which indicated that he had a certain level of sophistication in avoiding the things that had aided the identification of the perpetrator of the best-known case of a ransom: theLindbergh kidnapping. It is not clear how he could have reasonably expected to ever spend the money, fence it at a discount or otherwise profit. While Cooper made the familiar-from-fiction demand of non-sequentially numbered small bills, mass publicity over the Lindbergh case had long made it public knowledge that even with 1930s technology, getting non-sequential bills in a ransom was no defense against the numbers being logged and used to track down a perpetrator. In the Lindbergh case, fencing what he could as hot money and being very careful with what he did personally pass, the perpetrator had been caught through the ransom money nonetheless, with identification and handwriting evidence only brought in at the trial.[103]

Although unconscionably perilous by the high safety, training and equipment standards ofskydivers, whether Cooper's jump was virtually suicidal is a matter of dispute. The author of an overview and comparison ofWorld War II aircrew bail-outs with Cooper's drop asserts a probability for his survival, and suggests that like copycat Martin McNally, Cooper lost the ransom during descent. The mystery of how the ransom could have been washed into Tena Bar from any Cooper jump area remains.[104] The Tena Bar find anomalies led one local journalist to suggest Cooper, knowing that he could never spend it, dumped the ransom.[105]

According to Kaye's research team, Cooper's meticulous planning may also have extended to the timing of his operation, and even his choice of attire. "The FBI searched but couldn't find anyone who disappeared that weekend," Kaye wrote, suggesting that the perpetrator may have returned to his normal occupation. "If you were planning on going 'back to work on Monday', then you would need as much time as possible to get out of the woods, find transportation and get home. The very best time for this is in front of a four-day weekend, which is the timing Dan Cooper chose for his crime." Furthermore, "if he was planning ahead, he knew he had to hitchhike out of the woods, and it is much easier to get picked up in a suit and tie than in old blue jeans."[90]

The Bureau were more skeptical, concluding that Cooper lacked crucial skydiving skills and experience. "We originally thought Cooper was an experienced jumper, perhaps even aparatrooper," said Special Agent Larry Carr, leader of the investigative team from 2006 until its dissolution in 2016. "We concluded after a few years this was simply not true. No experienced parachutist would have jumped in the pitch-black night, in the rain, with a 200-mile-an-hour wind in his face, wearing loafers and a trench coat. It was simply too risky. He also missed that his reserve 'chute was only for training, and had been sewn shut—something a skilled skydiver would have checked."[80] He also failed to bring or request a helmet,[106] chose to jump with the older and technically inferior of the two primary parachutes supplied to him,[50] and jumped into a −70 °F (−57 °C) wind chill without proper protection against the extreme cold.[107][108]

The FBI speculated from the beginning that Cooper did not survive his jump.[80] "Diving into the wilderness without a plan, without the right equipment, in such terrible conditions, he probably never even got his 'chute open," said Carr.[4] Even if he did land safely, agents contended that survival in the mountainous terrain at the onset of winter would have been all but impossible without an accomplice at a predetermined landing point. This would have required a precisely timed jump—necessitating, in turn, cooperation from the flight crew. There is no evidence that Cooper requested or received any such help from the crew, nor that he had any clear idea where he was when he jumped into the stormy, overcast darkness.[73]

The 1980 cash discovery launched several new rounds of conjecture and ultimately raised more questions than it answered. Initial statements by investigators and scientific consultants were founded on the assumption that the bundled bills washed freely into the Columbia River from one of its many connecting tributaries. An Army Corps of Engineers hydrologist noted that the bills had disintegrated in a "rounded" fashion and were matted together, indicating that they had been deposited by river action, as opposed to having been deliberately buried.[109] That conclusion, if correct, supported the opinion that Cooper had not landed near Lake Merwin nor any tributary of the Lewis River, which feeds into the Columbia well downstream from Tina Bar. It also lent credence to supplemental speculation (see Later developments above) that placed the drop zone near the Washougal River, which merges with the Columbia upstream from the discovery site.[110]

But the "free floating" hypothesis presented its own difficulties; it did not explain the ten bills missing from one packet, nor was there a logical reason that the three packets would have remained together after separating from the rest of the money. Physical evidence was incompatible with geologic evidence: the FBI's chief investigator, Himmelsbach, observed that free-floating bundles would have had to wash up on the bank "within a couple of years" of the hijacking; otherwise the rubber bands would have long since deteriorated,[111]an observation confirmed experimentally by the Cooper Research Team (see #Subsequent FBI disclosures below).[90] Geological evidence suggested that the bills arrived at Tina Bar well after 1974, the year of a Corps of Engineers dredging operation on that stretch of the river. Geologist Leonard Palmer of Portland State University found two distinct layers of sand and sediment between the clay deposited on the riverbank by the dredge and the sand layer in which the bills were buried, indicating that the bills arrived long after dredging had been completed.[109][112] The Cooper Research Team later challenged Palmer's conclusion, citing evidence that the clay layer was a natural deposit. That finding, if true, favors an arrival time of less than one year after the event (based on the rubber band experiment), but does not help to explain how the bundles got to Tina Bar, nor from where they came.[113]

Retired FBI chief investigator Ralph Himmelsbach wrote in his 1986 book, "I have to confess, if I [were] going to look for Cooper, I would head for the Washougal."[96] The Washougal Valley and its surroundings have been searched repeatedly by private individuals and groups in subsequent years; to date, no discoveries directly traceable to the hijacking have been reported.[5] Some investigators have speculated that the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens may have obliterated any remaining physical clues.[114]

Alternative theories were advanced. Some surmised that the money had been found at a distant location by someone (or possibly even a wild animal), carried to the riverbank, and reburied there. The sheriff of Cowlitz County proposed that Cooper accidentally dropped a few bundles on the airstair, which then blew off the aircraft and fell into the Columbia River. One local newspaper editor theorized that Cooper, knowing he could never spend the money, dumped it in the river, or buried portions of it at Tena Bar (and possibly elsewhere) himself.[105] No hypothesis offered to date satisfactorily explains all of the existing evidence.[90]

Comments

Post a Comment