SIM

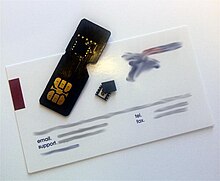

A mini-SIM card next to its electrical contacts in a Nokia 6233

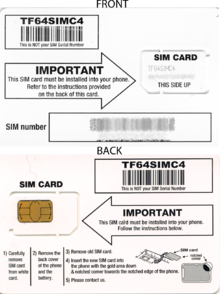

A TracFone Wireless SIM card has no distinctive carrier markings and is only marked as a "SIM CARD".

A subscriber identity module or subscriber identification module (SIM) is an integrated circuit that is intended to securely store theinternational mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) number and its related key, which are used to identify and authenticate subscribers onmobile telephony devices (such as mobile phones and computers). It is also possible to store contact information on many SIM cards. SIM cards are always used on GSM phones; for CDMA phones, they are only needed for newer LTE-capable handsets. SIM cards can also be used in satellite phones, computers, or cameras.

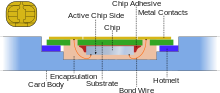

The SIM circuit is part of the function of auniversal integrated circuit card (UICC) physical smart card, which is usually made ofPVC with embedded contacts andsemiconductors. "SIM cards" are transferable between different mobile devices. The first UICC smart cards were the size of credit and bank cards; sizes were reduced several times over the years, usually keeping electrical contacts the same, so that a larger card could be cut down to a smaller size.

A SIM card contains its unique serial number (ICCID), international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) number, security authentication and ciphering information, temporary information related to the local network, a list of the services the user has access to, and two passwords: a personal identification number (PIN) for ordinary use, and a personal unblocking code (PUC) for PIN unlocking.

History and procurement

The SIM was initially specified by theEuropean Telecommunications Standards Institute in the specification with the number TS 11.11. This specification describes the physical and logical behaviour of the SIM. With the development of UMTS the specification work was partially transferred to3GPP. 3GPP is now responsible for the further development of applications like SIM (TS 51.011[1]) and USIM (TS 31.102[2]) and ETSI for the further development of the physical card UICC.

The first SIM card was developed in 1991 by Munich smart-card maker Giesecke & Devrient, who sold the first 300 SIM cards to the Finnish wireless network operatorRadiolinja.[3][4]

Today, SIM cards are ubiquitous, allowing over 7 billion devices to connect to cellular networks around the world. According to the International Card Manufacturers Association (ICMA), there were 5.4 billion SIM cards manufactured globally in 2016 creating over $6.5 billion in revenue for traditional SIM card vendors.[5] The rise of cellular IoT and 5G networks is predicted to drive the growth of the addressable market for SIM card manufacturers to over 20 billion cellular devices by 2020.[6] The introduction of Embedded SIM (eSIM) and Remote SIM Provisioning (RSP) from the GSMA [7] may disrupt the traditional SIM card ecosystem with the entrance of new players specializing in "digital" SIM card provisioning and other value-added services for mobile network operators.

Inactivation

Many non-contractual "pay-as-you-go" arrangements require the subscriber to actively use credit periodically to avoid account expiration, expiration period depends on network operators, typically defining a period from three months to one year. This is sometimes associated with the SIM card being made "inactive" by the network.[8]

Registration

Most countries and operators require customer identification to activate service, but some, such as The United States, Hong KongSAR, Lithuania and the Philippines, do not.

Design

There are three operating voltages for SIM cards: 5 V, 3 V and 1.8 V (ISO/IEC 7816-3 classes A, B and C, respectively). The operating voltage of the majority of SIM cards launched before 1998 was 5 V. SIM cards produced subsequently are compatible with3 V and 5 V. Modern cards support 5 V, 3 Vand 1.8 V.

Modern SIM cards allow applications to load when the SIM is in use by the subscriber. These applications communicate with the handset or a server using SIM Application Toolkit, which was initially specified by 3GPP in TS 11.14. (There is an identical ETSI specification with different numbering.) ETSI and 3GPP maintain the SIM specifications. The main specifications are: ETSI TS 102 223, ETSI TS 102 241, ETSI TS 102 588, and ETSI TS 131 111. SIM toolkit applications were initially written in native code using proprietary APIs. To provide interoperability of the applications, ETSI chose Java Card.[citation needed]. Additional standard size and specifications of interest are maintained by GlobalPlatform.

Data

SIM cards store network-specific information used to authenticate and identify subscribers on the network. The most important of these are the ICCID, IMSI, Authentication Key (Ki), Local Area Identity (LAI) and Operator-Specific Emergency Number. The SIM also stores other carrier-specific data such as the SMSC (Short Message Service Center) number, Service Provider Name (SPN), Service Dialing Numbers (SDN), Advice-Of-Charge parameters and Value Added Service (VAS) applications. (Refer to GSM 11.11[9])

SIM cards can come in various data capacities, from 8 KB to at least 256 KB. All can store a maximum of 250 contacts on the SIM, but while the 32 KB has room for 33Mobile Network Codes (MNCs) or network identifiers, the 64 KB version has room for 80 MNCs.[citation needed] This is used by network operators to store information on preferred networks, mostly used when the SIM is not in its home network but is roaming. The network operator that issued the SIM card can use this to have a phone connect to a preferred network that is more economic for the provider instead of having to pay the network operator that the phone 'saw' first. This does not mean that a phone containing this SIM card can connect to a maximum of only 33 or 80 networks, but it means that the SIM card issuer can specify only up to that number of preferred networks. If a SIM is outside these preferred networks it uses the first or best available network.

ICCID

Each SIM is internationally identified by its integrated circuit card identifier (ICCID). ICCIDs are stored in the SIM cards and are also engraved or printed on the SIM card body during a process called personalisation. The ICCID is defined by the ITU-T recommendation E.118 as the Primary Account Number.[10] Its layout is based on ISO/IEC 7812. According to E.118, the number is up to 22 digits long, including a single check digit calculated using the Luhn algorithm. However, the GSM Phase 1[11] defined the ICCID length as 10 octets (20 digits) with operator-specific structure.

The number is composed of the following subparts:

Issuer identification number (IIN)

Maximum of seven digits:

- Major industry identifier (MII), 2 fixed digits,89 for telecommunication purposes.

- Country code, 1–3 digits, as defined by ITU-T recommendation E.164.

- Issuer identifier, 1–4 digits.

Individual account identification

- Individual account identification number. Its length is variable, but every number under one IIN has the same length.

Check digit

- Single digit calculated from the other digits using the Luhn algorithm.

With the GSM Phase 1 specification using 10octets into which ICCID is stored as packed BCD, the data field has room for 20 digits with hexadecimal digit "F" being used as filler when necessary.

In practice, this means that on GSM SIM cards there are 20-digit (19+1) and 19-digit (18+1) ICCIDs in use, depending upon the issuer. However, a single issuer always uses the same size for its ICCIDs.

To confuse matters more, SIM factories seem to have varying ways of delivering electronic copies of SIM personalization datasets. Some datasets are without the ICCID checksum digit, others are with the digit.

As required by E.118, The ITU publishes a list of all current internationally assigned IIN codes in its Operational Bulletins.[12] As of October 2016 the list issued on 15 November 2013 was current.[13]

International mobile subscriber identity (IMSI)

SIM cards are identified on their individual operator networks by a unique International Mobile Subscriber Identity (IMSI). Mobile network operators connect mobile phone calls and communicate with their market SIM cards using their IMSIs. The format is:

- The first three digits represent the Mobile Country Code (MCC).

- The next two or three digits represent theMobile Network Code (MNC). Three-digit MNC codes are allowed by E.212 but are mainly used in the United States and Canada.

- The next digits represent the mobile subscriber identification number (MSIN). Normally there are 10 digits, but can be fewer in the case of a 3-digit MNC or if national regulations indicate that the total length of the IMSI should be less than 15 digits.

- Digits are different from country to country.

Authentication key (Ki)

The Ki is a 128-bit value used in authenticating the SIMs on a GSM mobile network (for USIM network, you still need Kibut other parameters are also needed). Each SIM holds a unique Ki assigned to it by the operator during the personalization process. The Ki is also stored in a database (termedauthentication center or AuC) on the carrier's network.

The SIM card is designed to prevent someone from getting the Ki by using the smart-card interface. Instead, the SIM card provides a function, Run GSM Algorithm, that the phone uses to pass data to the SIM card to be signed with the Ki. This, by design, makes using the SIM card mandatory unless the Kican be extracted from the SIM card, or the carrier is willing to reveal the Ki. In practice, the GSM cryptographic algorithm for computing SRES_2 (see step 4, below) from the Ki has certain vulnerabilities[14] that can allow the extraction of the Ki from a SIM card and the making of a duplicate SIM card.

Authentication process:

- When the mobile equipment starts up, it obtains the international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) from the SIM card, and passes this to the mobile operator, requesting access and authentication. The mobile equipment may have to pass a PIN to the SIM card before the SIM card reveals this information.

- The operator network searches its database for the incoming IMSI and its associated Ki.

- The operator network then generates a random number (RAND, which is a nonce) and signs it with the Ki associated with the IMSI (and stored on the SIM card), computing another number, that is split into the Signed Response 1 (SRES_1, 32 bits) and the encryption key Kc (64 bits).

- The operator network then sends the RAND to the mobile equipment, which passes it to the SIM card. The SIM card signs it with its Ki, producing SRES_2 and Kc, which it gives to the mobile equipment. The mobile equipment passes SRES_2 on to the operator network.

- The operator network then compares its computed SRES_1 with the computed SRES_2 that the mobile equipment returned. If the two numbers match, the SIM is authenticated and the mobile equipment is granted access to the operator's network. Kc is used to encrypt all further communications between the mobile equipment and the network.

Location area identity

The SIM stores network state information, which is received from the Location Area Identity (LAI). Operator networks are divided into Location Areas, each having a unique LAI number. When the device changes locations, it stores the new LAI to the SIM and sends it back to the operator network with its new location. If the device is power cycled, it takes data off the SIM, and searches for the prior LAI.

SMS messages and contacts

Most SIM cards store a number of SMS messages and phone book contacts. It stores the contacts in simple "name and number" pairs. Entries that contain multiple phone numbers and additional phone numbers are usually not stored on the SIM card. When a user tries to copy such entries to a SIM, the handset's software breaks them into multiple entries, discarding information that is not a phone number. The number of contacts and messages stored depends on the SIM; early models stored as few as five messages and 20 contacts, while modern SIM cards can usually store over 250 contacts.[citation needed]

Formats

Nano-SIM (in bottom), micro-SIM and mini-SIM, SIM brackets from Movistarin Colombia

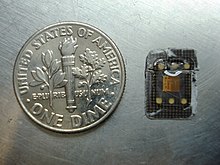

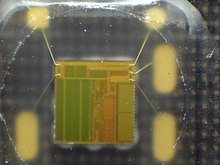

The memory chip from a micro-SIM card without the plastic backing plate, next to a US dime, which is approx. 18 mm in diameter

SIM cards have been made smaller over the years; functionality is independent of format. Full-size SIM were followed by mini-SIM, micro-SIM, and nano-SIM. SIM cards are also made to embed in devices.

Full-size SIM

The full-size SIM (or 1FF, 1st form factor) was the first form factor to appear. It has the size of a credit card (85.60 mm × 53.98 mm × 0.76 mm). Later smaller SIMs are often supplied embedded in a full-size card that they can be pushed out of.

Mini-SIM

The mini-SIM (or 2FF) card has the same contact arrangement as the full-size SIM card and is normally supplied within a full-size card carrier, attached by a number of linking pieces. This arrangement (defined in ISO/IEC 7810 as ID-1/000) lets such a card be used in a device that requires a full-size card – or in a device that requires a mini-SIM card, after breaking the linking pieces. As the full-size SIM is no longer used, some suppliers refer to the mini-SIM as a "standard SIM" or "regular SIM".

Micro-SIM

The micro-SIM (or 3FF) card has the same thickness and contact arrangements, but reduced length and width as shown in the table above.[15]

The micro-SIM was introduced by theEuropean Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) along with SCP, 3GPP(UTRAN/GERAN), 3GPP2 (CDMA2000), ARIB,GSM Association (GSMA SCaG and GSMNA),GlobalPlatform, Liberty Alliance, and the Open Mobile Alliance (OMA) for the purpose of fitting into devices too small for a mini-SIM card.[16][17]

The form factor was mentioned in the December 1998 3GPP SMG9 UMTS Working Party, which is the standards-setting body for GSM SIM cards,[18] and the form factor was agreed upon in late 2003.[19]

The micro-SIM was designed for backward compatibility. The major issue for backward compatibility was the contact area of the chip. Retaining the same contact area makes the micro-SIM compatible with the prior, larger SIM readers through the use of plastic cutout surrounds. The SIM was also designed to run at the same speed (5 MHz) as the prior version. The same size and positions of pins resulted in numerous "How-to" tutorials and YouTube video with detailed instructions how to cut a mini-SIM card to micro-SIM size.[20]

The chairman of EP SCP, Dr. Klaus Vedder, said[19]

- "ETSI has responded to a market need from ETSI customers, but additionally there is a strong desire not to invalidate, overnight, the existing interface, nor reduce the performance of the cards."

Micro-SIM cards were introduced by various mobile service providers for the launch of the original iPad, and later for smartphones, from April 2010. The iPhone 4 was the first smartphone to use a micro-SIM card in June 2010, followed by many others.

Nano-SIM

The nano-SIM (or 4FF) card was introduced on 11 October 2012, when mobile service providers in various countries started to supply it for phones that supported the format. The nano-SIM measures 12.3 × 8.8 × 0.67 mm and reduces the previous format to the contact area while maintaining the existing contact arrangements. A small rim of isolating material is left around the contact area to avoid short circuits with the socket. The nano-SIM is 0.67 mm thick, compared to the 0.76 mm of its predecessor. 4FF can be put into adapters for use with devices designed for 2FF or 3FF SIMs, and is made thinner for that purpose,[21] but many phone companies do not recommend this.[22][not in citation given]

The iPhone 5, released in September 2012, was the first device to use a nano-SIM card, followed by other handsets.

Embedded-SIM/embedded universal integrated circuit card (eUICC)

An upcoming new type of SIM is called e-SIM or eSIM (embedded SIM). It is a non-replaceable embedded chip in SON-8 package that is soldered directly onto a circuit board. It has M2M and remote SIM provisioningcapabilities.

The surface mount format provides the same electrical interface as the full size, 2FF and 3FF SIM cards, but is soldered to the circuit board as part of the manufacturing process. In M2M applications where there is no requirement to change the SIM card, this avoids the requirement for a connector, improving reliability and security. GSMA has been discussing the possibilities of a software based SIM card since 2010.[23] While Motorola noted that eUICC is geared at industrial devices, Apple "disagreed that there is any statement forbidding the use of an embedded UICC in a consumer product." in 2012,[24] The European Commission has selected the Embedded UICC format for its in-vehicle emergency call service known aseCall. All new car models in the EU must have one by 2018 to instantly connect the car to the emergency services in case of an accident. Russia has a similar plan with theERA-GLONASS regional satellite positioning system.[25]

Security

In July 2013, Karsten Nohl, a security researcher from SRLabs, described[26][27]vulnerabilities in some SIM cards that supported DES, which, despite its age, is still used by some operators.[27] The attack could lead to the phone being remotely cloned or let someone steal payment credentials from the SIM.[27] Further details of the research were provided at BlackHat on July 31, 2013.[27][28]

In response, the International Telecommunication Union said that the development was "hugely significant" and that it would be contacting its members.[29]

In February 2015, it was reported by The Intercept that the NSA and GCHQ had stolen the encryption keys (Ki's) used by Gemalto(the manufacturer of 2 billion SIM cards annually), enabling these intelligence agencies to monitor voice and data communications without the knowledge or approval of cellular network providers or judicial oversight.[30] Having finished its investigation, Gemalto claimed that it has “reasonable grounds” to believe that the NSA and GCHQ carried out an operation to hack its network in 2010 and 2011, but says the number of possibly stolen keys would not have been massive.[31]

Comments

Post a Comment